It seems like the words “school choice” have been identified by many as words that have become offensive in the lexicon of public education. Just as Auntie Maxine (Rep Maxine Waters (D-CA)) reclaimed her time on the floor of the US Congress, I want to reclaim this term. In Arizona school choice means that there is open enrollment for all school districts in the state. However, even the term “open enrollment” has been used as a dog whistle to mean “those kids” who don’t live in a particular neighborhood. With schools, for the time being, and hopefully at least until January 2021, going online, what does school choice look like as parents begin to send their children either back to their traditional school via online distance learning, or choose another option that might best fit their needs? School choice for a family is a personal matter. As we know, the personal is political. Choices are not made in a vacuum, and oftentimes with varying degrees of information, some valid and some not as valid. No matter what position one takes, concerning school choice, it is important to appreciate that every school is a “selective enrollment” school. Meaning, if you have the means to live in an area with high property taxes and good schools, you have made a selective, conscious choice. There is a saying in education that zip code should not determine your educational outcomes. Arizona, in having open enrollment, in theory has addressed this issue. In practice, there is something entirely different taking place. Even with most schools going online at least for the next month or two, the disparities and inequalities of what online looks like are tremendous. Some districts have the resources to purchase Chromebooks (or other laptops) and distribute them to every student (in what is called a 1:1 ratio), while others are scraping together funds to come up with technology for students in their districts. Same holds true for internet access. We know that there are companies who are working with districts in some areas to provide service, but still at a cost. In certain parts of urban and rural areas, even with the improvements, the service remains spotty. Lastly, and perhaps the most egregious, are the teachers and their preparation for online distance learning. Teaching in the age of a pandemic meant many teachers did not have a full summer of not only decompressing from a very challenging last quarter of school, but also the nontraditional task of having to start their planning and development for the 2020-21 academic year far earlier than usual. In regard to some teachers being reticent about returning to the physical classroom, people have quickly gone from hero worshiping teachers to demanding that they are somehow “weak” or “selfish” for not wanting to put their lives at risk by entering the classroom. Some have even gone so far as to compare them to other front-line workers. These false equivalencies are grounded in many ways by gender, but also by class. As I mentioned in my last blog about ‘pandemic pods,’ those who have a way for their child to be out of the classroom and still experience face to face learning have found a way, those who do not have that option, have not. They are the ones most in need of teachers who know how to provide brilliant social emotional connections as well as pedagogy for students who are longing to get back to learning. So, what is this learning going to look like for the foreseeable future? It depends on where you are and the familiarity your teacher has with both the training to provide online distance learning and their comfort level with the technology to implement said pedagogy. I was recently reminded of an fundamental theory that was the foundation for my dissertation work and something that I still hold as one of the most important aspects of a “good” school, no matter the structure (e.g., online, face to face, traditional, charter, etc…). Anthony Bryk in 2010 expanded on his work done in the early 2000s on trust in schools with Barbara Schneider to articulate five essential ingredients for school improvement. I would argue, these five tools should not only be a guide for schools that are in need of reforms, but also schools that are transitioning to online distance learning, or other forms of non-traditional instruction that will be needed as we move forward in public education.

Education, like so many things in our society, has been commodified and packaged. As such, many have employed the same mentality as if they were going shopping. If I can afford better, I should get better. Equity does not mean everyone has the same thing; it means that we make sure that the “least of thee” at least has everything they need to be successful. Schools are in the “business” of attracting us with the bells and whistles that they can provide, but they should also be in the “business” of creating opportunities for academic growth that include not just who has the most, but who learns about the diversity and complexities of this country. Schooling has changed and we, as parents, must quickly adapt, be equipped with important data, and use due diligence. In utilizing Bryk’s (2010) work, in my previous blog from 2016 I posted my version of the five qualities that signify a “good” school culture based on our search for a school for our first child when we he was about to enroll in kindergarten. Here is the updated list.

0 Comments

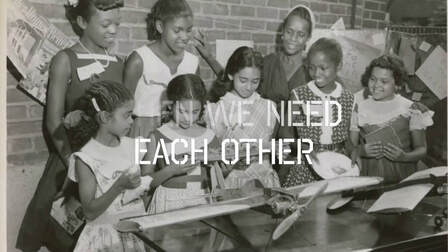

Welcome to 2020 and the twin pandemics of the flash point of George Floyd’s murder being livestreamed over the entire 8:46 it took for his life to be extinguished and the worldwide pandemic of COVID-19. This past March, many schools across the country were forced into utilizing 21st century technology due to the closure of school buildings and face-to-face instruction due to COVID-19. While there were many areas in which distance/online learning thrived, too many districts, schools and dare I say teachers, were unprepared not just for being online, but providing the type of social emotional needs, pedagogical innovations, and technological skill needed to be “successful.” As such, despite the brilliant efforts of many teachers to duct tape the Titanic together as it was sinking, because of their experiences this spring, many parents are hesitant to send their kids back into their bedrooms, kitchen tables or elsewhere in their homes to resume distance/online. And perhaps for good reason. Many districts were unable to quickly distribute laptops and internet connections for their students, and even those who were, if there were a limited number of resources, they were not always distributed equitably. For those students and families who already had hardware (e.g., computers), many of them lived in areas that were not equipped to withstand the broadband usage of everyone being online. A number of parents and students were not able to easily transition to online/distance learning due to their own technological learning curve. Another concern besides technology, is the realization that there are a significant number of parents who have legitimate childcare concerns and are unable to work from home while their children are there during school hours. This pandemic has really helped shine a light on the multitude of inequities that exists, not just racially in this country, but also in terms of class and accessibility. One response to this phenomenon is the advent of what the New York Times describes as ‘pandemic pods’ or ‘home schooling pods.’ These micro schools or conglomeration of families, neighbors or friends are created by either parents, or increasingly teachers, who organize smaller groups of children 6-10 or so, to congregate at a home to have physical interactions similar to school, and to be “taught” by someone who is being paid in excess of $1000 per child per month (depending on location). Just the price point alone is something that not many families who are in traditional public schools, or even many charters in urban districts, are able to afford. Childcare in this country has always been exorbitant in terms of cost, but this new segregation of public schools – pulling some children instead of others out of public schools for whatever period of time necessary until it is “safe” to return to their ‘home’ school has many unintended outcomes parents who choose this option may not have considered. Of course, safety is paramount, but equity needs to be factored in as well. As the emergence of pods come about as the school year approaches, it will be interesting to see how equitable they are. Even if we are only examining the cost aspects, since public schools (primarily) are free, this is a cost that many parents, especially during this uncertain time, are unable to withstand. Consequentially, pods have the potential to exacerbate the already profound inequities between school districts and even between schools in large school districts. Parents who can afford the technology and teacher will continue to provide a safe, educational learning environment (or at the very least the "socialization" they are so desiring after being isolated for months) for their children while those without will be relegated to non-profit programs and haphazard learning environments in which it is likely academic achievement will suffer if addressed at all. If we viewed ‘pandemic pods’ through the lens of being an opportunity to reimagine what schools look like in terms of population and pedagogy, pods could have the potential to shift the educational landscape for the future. Back in the 1960s when schools were at a crossroads because of the exodus of White families from urban neighborhoods and public schools, Freedom Schools were created to fill the gap for Black and Brown students across the country. Just like pods, Freedom Schools were a response to the closing of schools during a crisis. However, Freedom schools were designed to create educational equity and balance in an unbalanced landscape, and ‘pandemic pods,’ unless we implement purposeful intent, have the potential to create the opposite. An us versus them mentality is the string pulling at the heart of the inequities that exist in public schools across the country. Freedom schools were (and still are) brought about because of the need to educate students of color equitably, pods, as many are currently being proposed, need to be cautious so as to not perpetuate or even exacerbate the same inequalities found in traditional public schools. While some make the comparison of pods to charter schools, there are opportunities to make pods more equitable and serve populations of students who have traditionally been denied educational excellence and equity, and taught a diverse, culturally relevant curriculum. As they are currently being developed, the models that are being proposed seem as if they are more likely to exclude, rather than include diverse students, pedagogically appropriate strategies and curriculum, and important social and emotional supports for the students participating. One response to the appearance of being exclusionary has been the idea of a “scholarship spot” for one or two children. As two noted scholars Drs. R. L’Heureux Lewis-McCoy and Pedro Noguera pointed out in a Good Housekeeping article, even though diversity, in all its forms, is beneficial to positive student outcomes, if parents are altruistic or “woke” enough to even include students from other neighborhoods (who they may know from athletic teams, STEM competitions, music/arts, etc…), the “benefit of the doubt” will not fall in their favor in terms of being included in friendship groups or worse, if a child gets sick. I can imagine people asking, what is the solution? I would love to see the amount of energy, time and dollars being spent on research and create educational ‘pandemic pods’ that focus on assisting parents and teachers in finding resources that can help foster better social emotional connections and creative distance/online pedagogy and practice. I was fortunate to sit on one of my local district ad hoc committees assigned to create a return to school plan. I was on the social emotional committee. Many in the district both teachers and parents, fail to believe that students can create community online. Two examples I would like people to consider are Zoom groups adults/parents have created for a multitude of things from yoga, cooking classes, study groups, and yes, wine hours with friends. Young people too have created online communities on multiple social media sites as well as online gaming. They have created their own norms, policing, practices and camaraderie. While it is not perfect; nothing can replace the elation of hearing a yoga class exhale in person, clicking the glass of an old friend, or sliding into home plate to win the game, online can be used more to our advantage if we focused on such. Lastly, if people are insistent on creating pods or micro schools, please be cognizant of being inclusive as much as possible. When I say inclusive, that does not mean just reaching out to the only Black or Brown person you know to ask if they want to be a part of the ‘pandemic pod.’ Rather, in places where there is collaboration between the school district and the community, reach out to your home school principal or a social service agency and see what learning options are being considered for students who have varying learning styles, modalities, experiences. Hopefully more and more people will begin to consider the possibility of young people coming together with classmates they would not normally come into contact with. If we are to end these dual pandemics, we will need more than a vaccine, we will need to come from a place of love to truly help uplift not just those who look like us, have similar experiences, bank accounts or degrees, but to reach out (yes, even if it is a little further than you’ve gone before) to make sure that everyone has the ability to attain educational equity. If we do this now, maybe in the future, when we return to face to face instruction, the model for what is taught, how it is taught and to whom it is taught will be forever changed. Only then can we truly begin to feel as if we have attained real integration. |

|